Of all the great historical figures throughout humanity, I have

the greatest admiration for the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844-1900), who is having his 173rd birthday today (15th

October). Nietzsche was certainly one of the most iconic and controversial

thinkers that has ever emerged in human history. With a daring attitude, an

original perspective, and an intense caliber for words, Nietzsche’s philosophy

challenged everything that was already well-established before his era, and

inspired both awe and contention after his death. He has been labeled with a

whole spectrum of words, from ‘genius’, ‘visionary’, ‘prophet’ to

‘megalomaniac’, ‘sexist’, ‘racist’, or even ‘fascist’. This is understandable –

his ideas were so original that it would provide starting points for those who

wanted to engage with the puzzles of life, yet the ambiguities in his writings often

presented opportunities for those who wanted to distort his meanings

deliberately for nefarious purposes. Nietzsche was clearly a complicated man!

Nietzsche has inspired so many thinkers and philosophers

since his departure from humanity in the early 20th century. What is

more noticeable is his intense influence on the art of the 20th

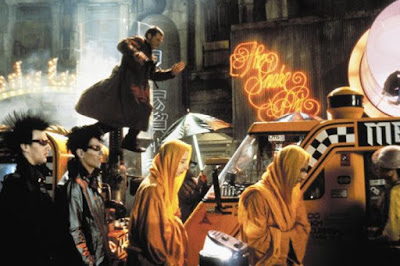

century – cinema. Nietzsche’s ideas have been explored in some of the greatest

films in the history of cinema, and his influence can be seen in the work

of many great filmmakers, including

Kurosawa, Welles, Peckinpah, Melville, Lang, Murnau, Bergman, Antonioni,

Herzog, Nolan, and of course the other protagonist of this article, Stanley

Kubrick. Heavily influenced by the great German philosopher’s work, many of Kubrick’s

films can be seen as the cinematic versions of Nietzsche’s ideas, like ‘2001: A

Space Odyssey’, ‘A Clockwork Orange’, ‘Full Metal Jacket’ and so on. For

‘2001’, this connection was even more evident when Kubrick used Richard

Strauss’ ‘Also Sprach Zarathustra’, the musical composition inspired by

Nietzsche’s magnum opus, to match the fantastic images of his film. Since

Kubrick often explored existentialist ideas in his films, it therefore should

not be surprising that they also overlapped with Nietzsche’s academic interests.

After all, you may not know much about Nietzsche’s story and ideas. Not to

worry – you have very likely quoted what Nietzsche has said long before this!

There are no facts, only interpretations.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

1.

What is the starting point for Nietzsche’s ideas? The

first major work of Nietzsche was ‘The Birth of Tragedy’, in which he provided

some original perspectives regarding ancient Greek culture. He identified two

important gods of the ancient times: Apollo and Dionysus. Apollo, the god of

sun, represented order, clarity, proportion, form and harmony. By contrast,

Dionysus, the god of wine, represented passion, intoxication, and art. Dionysus

was fascinating because he was in a constant state of chaos, and he often

threatened the established and formalized structure he encountered. He also

celebrated unconscious desires, sexuality, and the amorality of natural forces.

For Nietzsche, to be a great human being, it is not merely a

choice between the attitude of Apollo or Dionysus. It is a combination or

entanglement of the two contrasting spirits, and the interaction and development

should be continuous throughout life. Thus, it is invalid for some critics to

call Nietzsche ‘irrational’ or ‘over-emotional’, because from his very first

work he has already stressed the importance of both reason and passion. What concerned Nietzsche was that there were

since then a severe imbalance in terms of the two forces in Western culture.

Philosophy since the ancient Greece

seemed to treasure the spirit of Apollo, yet undermined or even negated the

Dionysian spirit as irrational or unconstructive. While the force of Dionysus

may seem destructive due to his passion and irrationality, it is also where the

traits of artistic talent and creativity originate. Thus, Nietzsche believed

that no matter how problematic our existence may be, we still have a chance for

redemption. That will only happen if we are willing to adopt the Dionysian

spirit and find solace in art.

One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.

- Friedrich Nietzsche

2.

If the duality of Apollo and Dionysus was important for

the well-being of humanity, then Kubrick was certainly an exemplary candidate

in this notion. With his original vision, Kubrick’s style represented an

amalgam of discipline and passion. He was rational in the sense that he

meticulously researched and prepared for his filmmaking projects, yet he

welcomed surprises and diversities at the many stages of filmmaking. When one looks at Kubrick’s formal and visual

strategy, one can easily see a parallel between his and Nietzsche’s beliefs.

The composition of Kubrick’s films consistently rely on a symmetric, highly

ordered one-point perspective, signifying the apparent ‘Enlightenment’ and

rationalism of Man’s endeavor and their actions to transform the world around

them. However, these balanced structures are often perturbed by the irrational

and instinctual urges of humanity, and this cycle of power struggle will just

continue indefinitely.

Inspired by Arthur Schopenhauer, both Nietzsche and Kubrick

believed the ecstatic energy of Dionysus and the impersonal Eros were very

similar to the concept of Will. Schopenhauer believed the world consisted of a

force known as ‘Will’. This intense life force is impersonal, purposeless, and

almost uncontrollable, yet it serves as the motivation for humanity’s very

existence. Schopenhauer also felt that the Will has expressed itself in many

forms of art, especially in music. To quote Schopenhauer – ‘In melody [we]

recognize the highest stage of the objectivation of the Will, that is, the

circumspect life and aspirations of man’. Nietzsche did find the Dionysiac

character in music, as it expressed the primal force of existence through the

sound and rhythm. Kubrick, taking inspirations from both Schopenhauer and

Nietzsche, compared, contrasted, and commented on his filmic images with the

unconventional use of pre-established music, and generated numerous cinematic

explosions in his films, completing altering the meanings of these cultural

artifacts thereafter.

Another similarity in terms of approach related to

Nietzsche’s view on the origin of Greek tragedy. Nietzsche maintained that the

theme behind Greek tragedy was an encounter between the material forces from

the Greek culture and the instinctual force from the Dionysiac spirit, rather

than serving as support or representation for some higher metaphysical truths

in Greek philosophy. The dramatic aspect of many Kubrick films were quite the same

– it was about how the instinctual urges inherent in humans could interact, or

even lead to conflict, with the artificial systems we have created for

ourselves.

Without music, life would be a mistake.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

3.

If things appeared to be the on track, then why did

Nietzsche see so many problems in the Western culture? What sort of status has

humanity reached for Nietzsche? Well, he felt that if we were motivated to give

some thoughts about these questions, we first had to be really honest and face

the music, even if it would turn out to be dark and negative. For Nietzsche,

the phenomenon of ‘modernity’ signified a displacement of power in the Western

civilization. Since the religious institutions of the West, especially of

Christianity, have lost the central power of governing the State, new powers

have be sought to govern and define the normality of the Western world since

the 17th century. This addressed Nietzsche’s famous statement, ‘God

is dead’. Nietzsche made painstaking efforts to show to his audience, given the

absurd situation of the Death of God, what have humans done and why the

consequence would just lead to an inevitable state of valueless existence - a

sense of nihilism.

After God is displaced, what sorts of power have arrived to

claim their places? These powers are rationality, science, humanism, and

teleological ideas. For many, the arrival of these ideas represented a departure

from dogmatism, and humans were therefore enlightened to become ‘modern men’.

With his biting critique, Nietzsche disagreed to this observation. For

Nietzsche, nothing fundamental has changed. While the use of reason or a ‘better’

outlook at humanity might sound like an improvement from a more primitive form

of existence, these approaches still could not address promptly to the

complexity of the human condition. By assuming that humans acted according to

reason, and that humans were innately capable of goodness, these ideas actually

undermined, or even deliberately denied, the truth of human nature - the

possession of irrational and dark sides of humanity. If we do not question the

assumptions of these rules and systems, and blindly believe and fit into them,

we soon will discover the limitations of these ‘golden rules’. Nietzsche

cautioned the people of his times, and those thereafter, that they were

situated in an age of decadence. If a new way of thinking and living could not be

devised, modern man would inevitably fall into a state of nihilism, the abyss

below the rope that signified human existence.

In heaven, all the interesting people are missing.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

4.

Kubrick also sensed a prevalence of decadence and nihilism

in the modern world, and he expressed this visually in his many masterpieces. In

‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, human interactions and the living environment have

become so sterile and banal that one may wonder whether these characters can

have genuine human emotions in such a technological world. Similar ideas can

also be seen in Antonioni’s 1960s films, and in John Boorman’s ‘Point Blank’

(1967), also in the same era and influenced by Antonioni. In ‘A Clockwork

Orange’, even with the prevalence of cultural artifacts, it cannot make the

characters more moral, or at least have better taste. The authoritarian control

cannot successfully undermine the barbarism inherent in all the characters,

good and bad. In ‘Barry Lyndon’, even if everything was ceremonial and appeared

to be of a high class, the characters were still dark from the inside, and

every character’s motivation was merely to fit into the painterly composition

of 18th century high culture. Finally in ‘Eyes Wide Shut’, the

characters were hypocritical in the polite society, the banal praises demanded

by the cultural machine made these statements meaningless, yet the greed and

will to exploit others were still present, albeit in a more systematic way in

the modern world. Kubrick and Nietzsche, while one century apart, were

expressing similar concerns that have stranded humanity through the Modern Age.

Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

5.

Where did all the problem regarding nihilism originate

from? Nietzsche’s major issue with all the established philosophy before him

was that they were metaphysical in stance. The philosophers believed that there

was an ultimate and transcendent truth, even if it would be totally

inaccessible and would only open to speculation. It was the apparent presence

of this ‘answer from the marking scheme’ that has led to unhappiness, or even nihilism

in our existence.

In order to organize better, humans have devised

institutions throughout the development or civilizations. Nietzsche has pointed

out that, no matter how logical, rational or civilized an institution or system

were established, it was often based on a hierarchical structure.

Unfortunately, this hierarchal arrangement had nothing to do with any objective

standard of good or bad – it was merely an aggressive assertion of power on the

strong ones onto those they despised or wanted to marginalize. Thus, one can

argue that there are no sound and foundational reasons for many of these

institutions to exist in the first place. They cannot claim that they exist in

the name of reason, for example - it is just they somehow win out in a

particular power struggle in the given context.

Nietzsche went as far to contend that, the very foundation

of rational thinking, the ability to categorize things and to establish binary

oppositions (the ‘yes/no’ dichotomy), was actually originated from a

self-interested motivation of marginalizing certain people or things in a

particular group or community. The irony is that this stereotyping exercise

eventually would become the modus operandi of subsequent philosophical thought.

Therefore, one cannot claim one theory is better than another theory because

the former is more rational or so – the former viewpoint just circumstantially

wins out in the power struggle.

And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

6.

Nietzsche also believed that a misunderstanding of

‘Nature’ was another reason why many thinkers have followed the wrong path. Nature,

as Nietzsche observed, was an amoral force of creation and destruction. It was indifferent

to justice, pity, or any ‘feel-good’ and sentimental moral ideas humanity has

ever created to give meaning to their lives. Because we have made the wrong

assumptions, we are led to believe that humanism, rationality, science and

organized religion can help us to understand ourselves and lead to a happier

existence. Yet, without a flexible mind for change, the most likely consequence

will just be the abyss staring back at you.

Thus, one can see that Nietzsche and Kubrick served an

anti-humanist viewpoint regarding the human condition. They reminded us not to

forget where we came from and our limitations. As Kubrick has stated in one

interview, ‘we are not born of fallen angels, but risen apes.’ Only with the

correct assumptions can lead to a better understanding of ourselves, and lead

to surprising revelations.

Morality in Europe today is herd animal morality.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

7.

Nietzsche was a famous Anti-Christ, and his contempt for

organized religion, especially Christianity, was legendary. Why did Nietzsche

have problems with Christianity? Well, personally I do not feel that he had any

prejudices against Christianity per se, as his ideas regarding Christianity

could be totally relevant to any organized religion. I have totally respect for

Christians and their faith, so I would say I cannot totally agree to

Nietzsche’s view in this respect.

The real reason why the self-proclaimed ‘Anti-Christ’ picked

on Christianity was due to the religion’s view on morality and the implications

it has exerted onto the Western culture. Nietzsche criticized Christianity of

advocating a sort of slave morality, which matched very well with the herd

instinct he found in his times in European culture. For him, one could be

categorized into either a master or a slave. A master is someone who is

assertive, confident and bold about what they believe in. A master is noble,

because he has his firm beliefs and does not need any approvals from others. A

slave is his very opposite – someone who is meek, weak, and have to follow

rules to show his obedience. The slave’s action is often motivated by guilt or

a fear for punishment. The slave’s antic matches well with the herd morality,

because someone who shows an intense level of individualism in a herd will tend

to be considered as a maverick and not following the order, and his action will

be scorn at rather than celebrate. Nietzsche delivered a knock out to

deconstruct Christianity – if someone is pure of heart, and commit to what they

believe in (even if that will lead to a negative consequence), why will he

weigh on whether to take action or not, based on whether the action will be

rewarded (e.g. a ticket to the heaven), or whether he will be punished as a

result? Is it, after all, a hypocritical motivation to start with?

An important attribute for the slave morality was

re-sentiment. For Nietzsche, re-sentiment was a passive attitude motivated by

hate. It was the inability to admire and respect. The re-sentiment mindset

demanded one to hate and have the feeling of being pushed by others, and to

distribute personal responsibilities towards the others. It was an important

pillar of slave morality, in which one would not even bother to question

whether he/she could master his life and address the pitfalls in an affirmative

manner.

There is more wisdom in your body than in your deepest philosophy.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

8.

Kubrick was critical of institutions as much as

Nietzsche. In many of his films, Kubrick questioned whether culture, rituals,

disciplinary systems and organized religion could lead to an increased sense of

morality of people. Through a satirical lens, Kubrick showed the miserable

outcome – the characters became flat and dehumanized when they had to obey the

systems, and the systems could still not address to contingencies on many

cases.

9.

You still believe your Socratic rationalization can

de-mystify the chaotic universe around you? What are you, a blockhead?

10.

Objective morality, a self-satisfying Enlightenment, a

fusion with the Absolute – they appear to be the pillars of human intelligence

and rationality – not to Nietzsche.

11.

Humanity seems to be in need of some sort of a deity to

make sense of everything. Is it merely a psychological need or a lack of

self-confidence and assertion?

12.

You, warrior of life, do not merely ask for a fair game,

but strive hard for victory.

What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

13.

Of all of Nietzsche’s work, 'Also Sprach Zarathustra' ('Thus Spoke Zarathustra') clearly stands out. This book was Nietzsche’s gift to humanity, and it

demonstrated Nietzsche’s masterful use of language to convey above-human ideas.

The book is special because while it is told in a fictional and more abstract

manner than his later work, ‘Zarathustra’ encompassed almost all of Nietzsche’s

most important ideas. Not only it is intensely inspiring, I also find it a

highly enjoyable book, and whenever I am depressed, this book will give me the

courage and confidence to continue and strive. ‘Zarathustra’ has led to two

further pieces of fine art for humanity – Richard Strauss’ ‘Also Sprach

Zarathustra’ and of course, Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’.

In the book, Zarathustra was a fictional character from

Nietzsche, who was very much speaking on behalf of Nietzsche. Zarathustra had a

lot of ideas and insights, but he was lonely, because no one understood what

the heck he was talking about, and the people did not bother to listen to

Zarathustra. As Zarathustra has mocked himself, he was the wrong mouth for

their ears. ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’ explored a number of key themes – the

evolution of Man, the meaning of life without God, the possibility of

‘over-man’, and eternal recurrence.

I will teach men the meaning of their existence – the overman, the lightning out of the dark cloud of man.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

14.

Nietzsche speculated the potential evolution of man. He

felt that man was currently ‘a rope tied between beast and superman – a rope

over the abyss’. Humanity is on the way to become what Nietzsche has always

dreamed of – the Übermensch (over-man). We have to strive in this direction, to

eventually become a nobler sort of person. He had also another analogy – ‘The

Three Metamorphoses’ – in the book. It was the transformation from the camel to

the lion, than to the final stage of a child. The transformation signified the

change of an agency from ‘Thou Shalt’ – order given by others – to ‘I Will’ –

assertion that comes out from oneself.

Kubrick was evidently inspired by these when he made ‘2001:

A Space Odyssey’. From Moonwatcher, Dave Bowman, to the Start Child, it

appeared as if version of ‘The Three Metamorphoses’, especially having Dave

walking on a tight rope – where he was in the outer space.

What does not kill me makes me stronger.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

15.

What are the attributes of the Übermensch? Well, the Übermensch

represents an affirmative vision of life, as he/she has already looked beyond

the negative aspects of nihilism, re-sentiment and the slave morality. He is

someone, quite literally, beyond good and evil. He embraces, and committees to

the will of power, which is to look for meanings and responsible for his own

existence, rather than looking beyond life for some transcendental reason or

universal morality.

The Übermensch is constantly overcoming himself – his own

fears, an appreciation of his own values and meaning, and his ability to create

values for himself. Because these are tough challenges, the Übermensch requires

a tremendous courage and self-confidence. Here is the motto from the Übermensch - 'Become who you are'!

You must become who it is that you are.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

16.

The concept of Übermensch has been distorted and

misused, as many sees its meaning as ‘overcoming others’, which is to say

harming or even eliminating others. While Nietzsche’s original formulation of

the idea might be ambiguous, it should be clear from close reading Nietzsche

did not include the destruction of another individual as an attribute of the Übermensch.

What we have to be cautious, through, is that Nietzsche seems to imply that the

Übermensch is amoral, or has his own code of morals. Thus, objectively we

cannot rule out the action from an Übermensch - or ‘Nietzschean strongs’, as

contrasting with ‘Nietzschean weaks’, who are those governed by a slave

morality – can lead to negative impacts for the others.

Kubrick has expressed this duality in many of his films. One

can see characters like the Moonwatcher, Dave Bowman, Alex Delarge, Redmond

Barry, and Napoleon (if Kubrick has made the film) can be considered

Nietzschean strongs, as they are daring and original for their times and

surroundings, yet during the process they have also committed acts that have

impacted the others’ well-being, including destruction and even murder. This is

the paradox of the ‘evil genius’, and I suppose why the Übermensch is a

far-reaching aim.

The noble human being honours himself as one who is powerful, also as one who has power over himself, who knows how to speak and be silent.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

17.

How should we philosophize about our existence?

Nietzsche urged us to think about the meaning of life, rather than speculating

issues that took place in another Platonic realm that we would never access. And,

due to the view of perspectivism, it may not only have one final answer to all

the questions regarding life. There can be many interpretations regarding the

very same issue, and no one answer can claim authority on others. Nietzsche has often encouraged us to think

about questions in a concrete, rather than abstract point of view, as it is far

more relevant for our existence. Very much like a Modernist, Nietzsche demanded

us to be critical about any knowledge that has fed to us or we have long taken

for grant. He especially urged us to embrace those things we have been led to

believe as bad or evil. While this may be a bit of a stretch, I feel

Nietzsche’s motive is to ask us to have a healthy skeptical attitude and to

really look beyond the obvious, and philosophize the underlying reason why

something is presented to us in a certain way.

he who knows fears but conquers fear , who sees the abyss, but with pride.

-Friedrich Nietzsche

18.

While Kubrick’s outlook was very similar to Nietzsche in

many aspects, he seemed to reverse the direction of Nietzsche’s abstract / concrete

dichotomy. Both thinkers have emphasized the importance of corporeality to

human existence, and yet Kubrick liked to start from the concrete side. By

addressing the corporeality side of human nature, we are made aware of our

animalistic limitations, and can thus look beyond the hubris and pretensions we

have made ourselves happier. As many critics have pointed out, the final aim is

to point back to the abstract and universal truths. Kubrick believed there were

some timeless truths of human nature, independent of the context or the era the

story took place in. The audience had to be able to detach these aspects from

the context of the story to gain insights that might lead to a better

appreciation of themselves.

Send your ships into uncharted seas!

-Friedrich Nietzsche

19.

In order to inspire his readers to see things in new

light, Nietzsche devised a number of absurd situations in his philosophy.

First, he advocated the attitude of 'Amor Fati' - the love of fate. Nietzsche

questioned the need for the 'Free will / determinism' debate to exist at all.

He felt that even if fate existed, the question was not how we could change it,

or run away from it. The most important issue is how we can face it with a

positive and affirmative attitude, no matter how effed up or absurd it would

turn out to be. Even the negative things

may have a new meaning, if we are willing to view it from a different

perspective.

Second, Nietzsche proposed the absurd condition of the

‘eternal recurrence’. Imagine if we have to live our own lives again and again,

until eternity. There is no way you can change the narrative of your life

story, you will have to experience exactly all the highs and lows in your life

again. Will you accept all these, and will you make the most of your life so

that you will not regret? Nietzsche believed that if we were willing to

understand this, we will commit to live our lives to the fullest, and be

affirmative about all the pitfalls throughout our very existence.

Finally, Nietzsche proposed the idea of the ‘Last Man’. It

is the final stage before the transformation to the over-man. When one is

individualized and acts according to his beliefs, a tremendous sense of

loneliness and alienation will follow, because now he does not have the comfort

of being part of the herd, and thus cannot just receive passively about what to

do. Standing on a cliff, the ‘Last Man’ becomes the master of his own life,

looking down at the herd, very much like Zarathustra’s case.

The secret of realizing the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment of existence is: to live dangerously!

-Friedrich Nietzsche

20.

What advice did Nietzsche provide us to face life in an

affirmative manner? To start with, Nietzsche wanted one to love his own life, right

now and right here. There was no point to ask for a better next life, or a

passport to heaven. You should discover gratifications from the experience of

your own existence. Even if there are adversities throughout life, Nietzsche

advised us to accept and embrace our mistakes and learn from it, not to turn

away from it or pass the responsibilities to some irrelevant parties. Finally,

Nietzsche wanted us to laugh - and had a good sense of humor. Because he

believed if we were willing to accept life in an affirmative attitude, and appreciated

life as a means to self-knowledge, one could not only live boldly but also

gaily, and the gratifications would surely emerge.

Concluding Remarks

Both Nietzsche and Kubrick stressed the importance of

self-knowledge – knowledge and insights that you discover only from yourself. A

better understanding of yourself can direct your concentration to the relevant

aspects, and you will have the courage to live a fulfilling life. Even if this

article can lead you to an intense fascination with Nietzsche and Kubrick, that

is not enough. Because only you can lead the motivation to change yourself, and to become the master of

your life. It is all in your hands.

by Ed Law

15/10/2017

Film Analysis